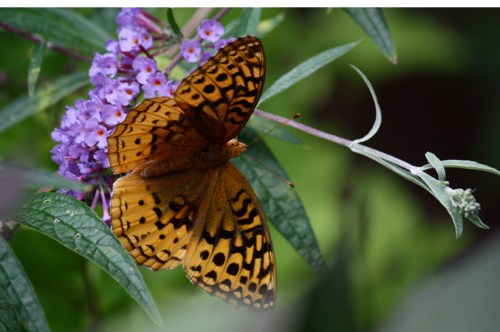

Singularly beautiful—large and rounded with tawny orange wings checkered with black dots and dashes—when observed from above. When wings are folded, this fritillary shows a striking underwing pattern of spangled spots, bordered by a wide yellow band and outlined in iridescent crescents. Perhaps the Great Spangled Fritillary has graced your garden. I had never encountered this creature of extraordinary beauty until the summer after we planted violets dug from a wildly unkempt cemetery. They were native common violets (Viola sororia). I don’t recommend the common violet for a small garden, unless you desire a garden composed entirely of common violets. Please don’t misunderstand; I do not regret planting V. sororia because otherwise I may never have encountered the Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele). No, I am glad to have welcomed this beauty to our garden. There are, however, far better behaved violets that are of equal importance to the fritillary caterpillars and they would be a far better choice for the garden. Both native wildflowers Labrador violet (Viola labradorica) and Canada violet (Viola canadensis) naturalize readily, making rulier groundcovers than common violets, and are lovely when in bloom and when not in flower.

O wind, where have you been,

That you blow so sweet?

Among the violets

Which blossom at your feet.

The honeysuckle waits

For Summer and for heat

But violets in the chilly Spring

Make the turf so sweet.

—Christina Rossetti (1830—1894)

The Great Spangled Fritillary is found throughout New England and its range extends from southern British Columbia and central Alberta, east across southern Canada and the central US to the Atlantic seaboard. It is one of three Greater Fritillaries found in our region, along with the Aphrodite and Atlantis Fritillaries. The wingspan of the Great Spangled Fritillary measures approximately three inches, compared to that of several of the smaller fritillaries found in our area, the Silver-bordered Fritillary and Meadow Fritillary, which measure about half as much. Its habitat is woodland openings, meadows, prairies, and other open habitats where violets and nectar plants such as common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), spotted Joe-pye weed, and ox-eye daisy are found.

Kingdom: Anilmalia (Animal)

Phylum: Arthropoda (Arthropods)

Class: Insecta (Insects)

Order: Lepidoptera (Butterflies, skippers, and moths)

Superfamily: Papilionoidea (Butterflies, excluding skippers)

Family: Nymphalidae (Brush-footed butterflies)

Subfamily: Heliconians

Genus: Speyeria

Species: cybele

Ancient cultures valued violets for their medicinal and aromatic properties. In art and literature they symbolize a widely varying range of human experiences from new life in spring to death and dying, young love, and frailty. The genus Viola comprises some 400 to 500 species, distributed around the world. Viola, often called pansies, violets, and heartsease, have been traditionally used to create perfumes, dyes, insecticides, soaps, expectorants, and analgesics for labor pain. The flowers and leaves of the violet plant make a delicious and nutritious addition to a garden salad; the leaves are rich in a variety of powerful chemicals including flavenoids, saponins, and glycosides.

The Greater Fritillaries have a unique and highly evolved association with violet plants. In late summer or early fall, the female oviposits eggs close to the ground on twigs or foliage near to, not necessarily on, a clump of violet plants. Newly emerged caterpillars crawl to the nearby hostplant. Rather than feed on the foliage, they nestle into the leaf litter at the base of the plant and enter diapause. For northern butterflies this behavior is thought to be an adaptation to cold weather since undigested food particles in the gut of a diapausing caterpillar would form ice crystals, thereby killing the larvae (Cech and Tudor). Diapause in insects is a physiological state of dormancy in response to predictable periods of adverse environmental conditions—winter in the case of the Greater Fritillaries.

In early spring, the awakening caterpillars, which are black with black protruding spines dotted red at the base, feed on freshly emerging violet shoots. The caterpillars pupate, and after metamorphosis, in late spring or early summer, the male Greater Fritillary butterflies begin to emerge, well before the females. Active courtship ensues once the females emerge. The females typically mate once, after which the males die off. The females live on during the summer in a temporary state of reproductive diapause, until ovipositing eggs in the late summer or early fall. Typically the Great Spangled Fritillaries that we encounter at this time of year are the females.

While photographing Great Spangled Fritillaries at high noon I noticed that the iridescence was quite apparent, although only showing for a fraction of a second. The photo below illustrates clearly the structural iridescent scales (or “spangles”). What the photo does not show is that the large whitish-looking spots also have iridescent hues of pearly pinkish-bluish-greenish.

Iridescence in Butterfly Wings

Butterflies, moths, and skippers are members of the insect order Lepidoptera; the name is derived from Greek lepidos for “scales” and ptera for “wings.” Their scaled wings distinguish them as a group from all other insects. Unrivalled in the living world, their wings are adorned with myriad patterns and solid colors in the full spectrum of the rainbow, as well as pure iridescent hues of blue, green, and violet.

The foundation of the Lepidoptera wing consists of a colorless, translucent membrane supported by a framework of tubular veins, radiating from the base of the wing to the outer margin. They are covered with thousands of overlapping scales, arranged very much like overlapping shingles on a roof. Like miniature canoe paddles, the scales are attached to the wings by their “handles.” So small that they feel like and are a similar size to the silky granules of face powder, their purpose is multi-fold. Scales protect and act as an aid to the aerodynamics of the entire wing structure, help regulate Lepidoptera temperature, and are the cells from which color and patterns originate. This color and patterning are used for sexual signaling and as a means of eluding birds and other would-be predators.

There are two fundamental mechanisms by which color is produced on the wings of Lepidoptera. Ordinary color is due to organic pigments present that absorb certain wavelengths and reflect others. Extraordinary iridescence on butterfly wings is caused by the interference of light waves due to multiple reflections within the physical structure of the individual scales. Iridescent scales are composed of many microscopic thin layers; each scale has its own color, from pigment present and from the diffraction of light on the surface (the surface of iridescent scales are intricately corrugated and grooved). The iridescent effect is created much like a prism and is called structural coloration. When viewed under a microscope, the iridescent scales of some species of butterflies have a similar appearance to that of the tiered layers of a pine tree. Sometimes structural color and pigmented color occur simultaneously and a secondary color is created in the usual way color is added. For example, when blue iridescent color is produced from the structure of a scale that also contains yellow pigment, the resulting color is iridescent green.

When Lepidoptera with iridescent scales fly, the surface of their wings continually change from brilliant hues to the underlying relatively duller scales of the wings, as the angle of light striking the wing changes. The ability of the Lepidoptera to rapidly change colors and patterns is one of their defense mechanisms against predators. Along with their undulating pattern of flight and the figure-eight movement of their wings, the effect is of ethereal flashes of light disappearing and reappearing.

Excerpt from Oh Garden of Fresh Possibilities! Chapter 15 ~ Flowers of the Air, pages 130-131.